Distribution History of the Bray Cartoons

Introduction

Chronologically, the major distributors of the Bray cartoons were Pathe, Paramount, Goldwyn Pictures, W. W. Hodkinson, Standard Cinema Corporation, and Film Booking Offices of America. For a time in the 1920s, Bray independently distributed "The Bray Magazine" on the states rights market; this split-reel generally recycled pre-existing components.

The original Bray theatrical cartoons were shot and distributed on 35mm nitrate film stock. It is assumed that readers are familiar with the historically unstable nature of nitrate stock and its propensity for deterioration (see Wiki: Nitrate Film). This, coupled with neglect and disposal of "outdated" films, account for the startlingly low rate of silent film survival. Bray avoided many studios' pattern of intentional neglect; corporate records show that J. R. Bray kept nearly all of his original output in a vault which was inspected every so often. However, there was no widespread knowledge of proper film preservation at the time, considering that nitrate stock was still in general use. A vault log of the Bray film holdings shows that a good number of element had "melted" and were subsequently discarded during inspections in 1937, 1941, and so forth. Other notations include a trend of intertitles "going bad" before the rest of the film stock deteriorated, thus needing replacement.

Even as late as the 1970s, studio staff unknowingly contributed to the additional deterioration of Bray's own newer, 1950s-era 16mm safety film negatives (see "Television" below). The damage was done by using processes to coat the films in order to hide scratches, as per film lab documents. Animation historian Ray Pointer confirms the outcome of this during early 1970s research in his web article _Finding Ko-Ko_: "...I contacted the Bray Studios and discovered that they did have a number of their old cartoons available in 16mm, including some ten Out of the Inkwell films made between 1919 and 1921. Naturally, I wanted to buy them all. I ordered two, The Clown's Pup (1919) and Automobile Ride (1921). I waited about two months, and then received a polite letter explaining that there were problems with these old negatives. I accepted prints of The Chinaman and The Tantalizing Fly as substitutes. I wanted to buy more, but the negatives already were deteriorating." (paragraph 5).

Despite the many reasons for 'film extinction,' one of the important aspects of the Bray Animation Project has been great efforts and successes made in locating film prints. While the Pathe-era films are the most difficult to locate, we have had much luck in uncovering many films that researchers and historians may not have thought they could one day view. The following guide tells of the most mainstream methods by which the Bray cartoons were distributed both commercially and for home use.

The original Bray theatrical cartoons were shot and distributed on 35mm nitrate film stock. It is assumed that readers are familiar with the historically unstable nature of nitrate stock and its propensity for deterioration (see Wiki: Nitrate Film). This, coupled with neglect and disposal of "outdated" films, account for the startlingly low rate of silent film survival. Bray avoided many studios' pattern of intentional neglect; corporate records show that J. R. Bray kept nearly all of his original output in a vault which was inspected every so often. However, there was no widespread knowledge of proper film preservation at the time, considering that nitrate stock was still in general use. A vault log of the Bray film holdings shows that a good number of element had "melted" and were subsequently discarded during inspections in 1937, 1941, and so forth. Other notations include a trend of intertitles "going bad" before the rest of the film stock deteriorated, thus needing replacement.

Even as late as the 1970s, studio staff unknowingly contributed to the additional deterioration of Bray's own newer, 1950s-era 16mm safety film negatives (see "Television" below). The damage was done by using processes to coat the films in order to hide scratches, as per film lab documents. Animation historian Ray Pointer confirms the outcome of this during early 1970s research in his web article _Finding Ko-Ko_: "...I contacted the Bray Studios and discovered that they did have a number of their old cartoons available in 16mm, including some ten Out of the Inkwell films made between 1919 and 1921. Naturally, I wanted to buy them all. I ordered two, The Clown's Pup (1919) and Automobile Ride (1921). I waited about two months, and then received a polite letter explaining that there were problems with these old negatives. I accepted prints of The Chinaman and The Tantalizing Fly as substitutes. I wanted to buy more, but the negatives already were deteriorating." (paragraph 5).

Despite the many reasons for 'film extinction,' one of the important aspects of the Bray Animation Project has been great efforts and successes made in locating film prints. While the Pathe-era films are the most difficult to locate, we have had much luck in uncovering many films that researchers and historians may not have thought they could one day view. The following guide tells of the most mainstream methods by which the Bray cartoons were distributed both commercially and for home use.

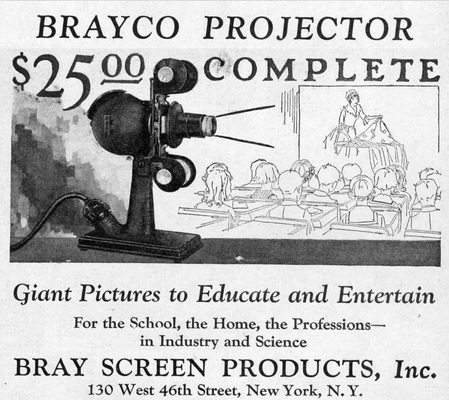

The Brayco Filmstrip Projector

Bray’s answer to the fire hazard and bulk of 35mm film was the development of the “Brayco” Film Strip Projector and its line of educational filmstrips, consisting of single-frame reproductions from Bray's educational motion pictures. This was a practical and economic solution for schools, since the process reduced a reel of 1000 feet to a six-foot strip. The projector sold for $25 and was simple to operate. This, combined with the obvious features of lower cost and ease in storage, made Bray Educational Filmstrips attractive to school systems. But Bray abandoned the format in the mid-1920s, with the introduction of 16mm safety film. Bray’s underestimation of the filmstrip's future was quite miscalculated, as this format continued to be a vital audio-visual tool well into the 1980s.

- Ray Pointer

Left: Brayco Projector ad, ca1924.

Below: Peter Rabbit Brayco strips from 1924 scanned and put into motion. Special thanks to YouTube user BadRonaldUeno

- Ray Pointer

Left: Brayco Projector ad, ca1924.

Below: Peter Rabbit Brayco strips from 1924 scanned and put into motion. Special thanks to YouTube user BadRonaldUeno

United Projector & Film Corp. (mid 1910s to early 1920s)

The United Projector & Film Corp. was a firm with offices in Buffalo, NY and Pittsburgh, PA. United was one of the first independent non-theatrical distributors of mainstream entertainment and educational films to utilize the 28mm format.

The 28mm gauge was invented in 1912 as a safety film stock for non-theatrical use, much the same way 16mm would later be treated (from 1923). Although 28mm was extremely popular in France and the UK, United and Pathe both offered large libraries of 28mm subjects in the United States as well. Both firms offered dozens if not hundreds of Bray subjects - both animated and live action - from the studio's pre-1922 film backlog. Insofar as these films were printed on safety stock, many 28mm Bray prints still survive today, and approximately three dozen examples have been collected here.

Right: Canister for United print of Bobby Bumps' Last Smoke

Below: Title card from United prints. Note the several references to safety film not requiring fire prevention safeguards during projection.

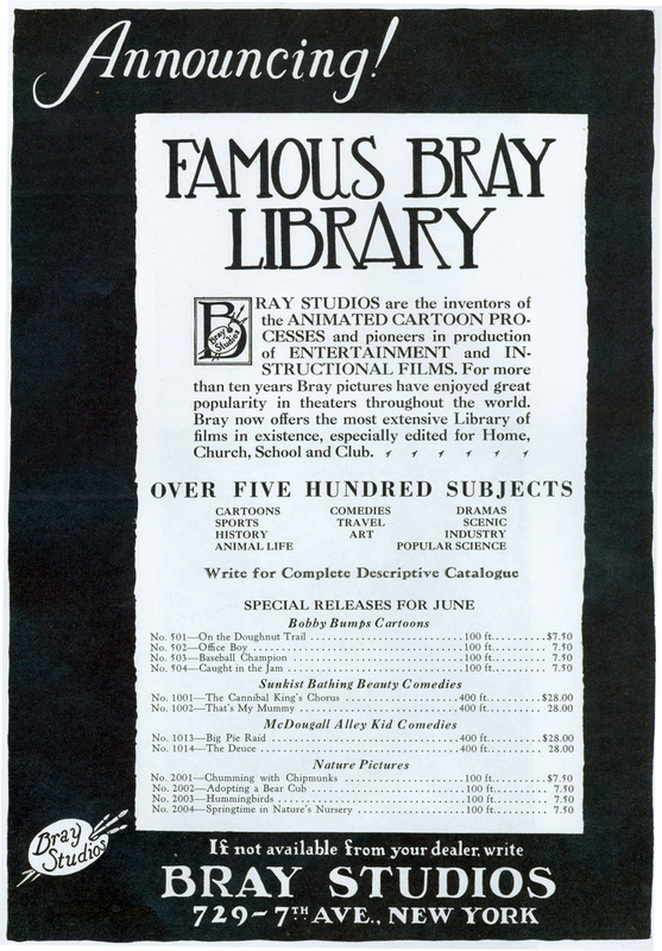

Bray Non-Theatrical (1921-1940s)

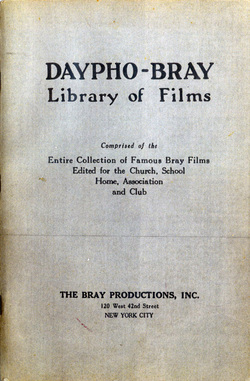

The Bray Studios began offering nearly its entire library of subjects in 1921. The initial rental/purchase catalog offers titles dating back to 1915 - if not earlier - though the format offered is vague: the catalog does not specify whether the prints are 28mm, 35mm, or both.

Later in the 1920s and through the 1940s, Bray printed and distributed catalogs of 16mm offerings. Surviving rental/sale prints originating with these catalogs - and not associated with the other distributors listed on this page - are sadly hard to find today, however, perhaps because the films' content made them less popular on the 16mm market than other distributors' titles. As an additional factor, Bray seems not have promoted its non-theatrical line to any great extent, which could also account for scarcity of prints.

Left: Daypho-Bray Library catalog cover, ca. 1921. At present nothing is known about the Daypho connection, except that the Daypho name seems to have been linked to the first non-theatrical Bray film library.

Below: Advertisement for 16mm home use prints from a 1929 issue of Movie Makers.

Kodascope Libraries (1923-1942)

The Kodascope Libraries were a network of rental libraries founded by the Eastman Kodak Co. in 1923. For a very short period at the start, Kodascope offerings were distributed in 35mm, but the library of subjects is best known for its high quality 16mm prints.

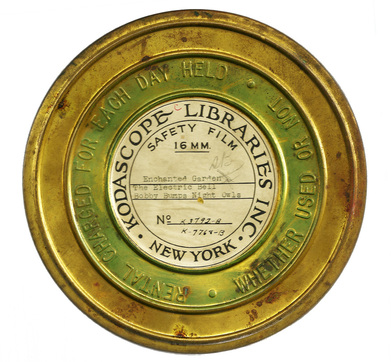

Kodascope offered a small handful of Bray subjects in its standard catalog, such as Col. Heeza Liar Plays Hamlet (1916). However, it is a little-known fact that local Kodascope libraries also absorbed locally-sold 16mm elements that were neither printed by Kodak itself offered in the standard Kodascope catalog. For example, one can find Kodascope reels and cans - with Kodascope accession numbers, typed on Kodascope labels - containing prints that originated with Hollywood Film Enterprises and other distributors of the time.

Thus, while Kodak itself evidently printed only a relative few Bray 16mms, additional Bray subjects can be found among local Kodascope library holdings. The source of these prints was likely Bray's non-theatrical 16mm line itself.

Left: Kodascope canister and reel containing three 16mm Bray subjects incorporated into the rental library. All three films are examples of titles not listed in published Kodascope catalogs, supporting the idea that virtually any Bray film could turn up in a Kodascope can.

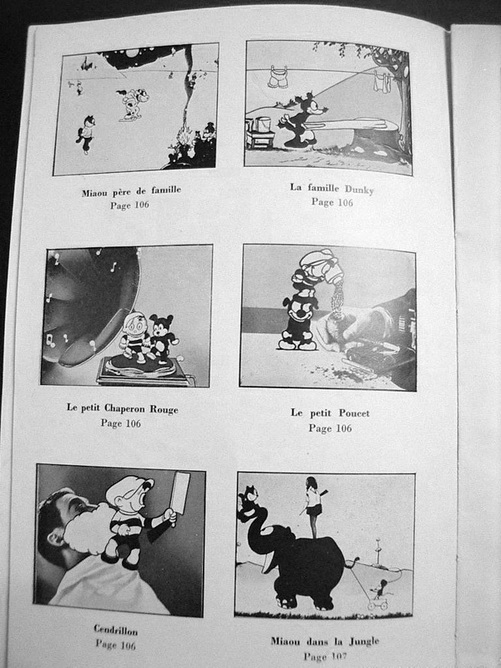

Below: Page from 1930s French Kodascope catalog showing some Dinky Doodle offerings.

Kodascope offered a small handful of Bray subjects in its standard catalog, such as Col. Heeza Liar Plays Hamlet (1916). However, it is a little-known fact that local Kodascope libraries also absorbed locally-sold 16mm elements that were neither printed by Kodak itself offered in the standard Kodascope catalog. For example, one can find Kodascope reels and cans - with Kodascope accession numbers, typed on Kodascope labels - containing prints that originated with Hollywood Film Enterprises and other distributors of the time.

Thus, while Kodak itself evidently printed only a relative few Bray 16mms, additional Bray subjects can be found among local Kodascope library holdings. The source of these prints was likely Bray's non-theatrical 16mm line itself.

Left: Kodascope canister and reel containing three 16mm Bray subjects incorporated into the rental library. All three films are examples of titles not listed in published Kodascope catalogs, supporting the idea that virtually any Bray film could turn up in a Kodascope can.

Below: Page from 1930s French Kodascope catalog showing some Dinky Doodle offerings.

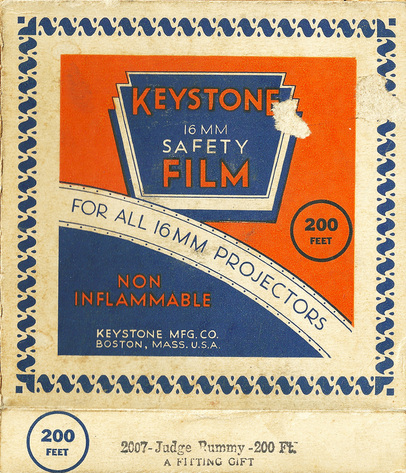

Keystone Manufacturing Co. (1932-mid 1940s)

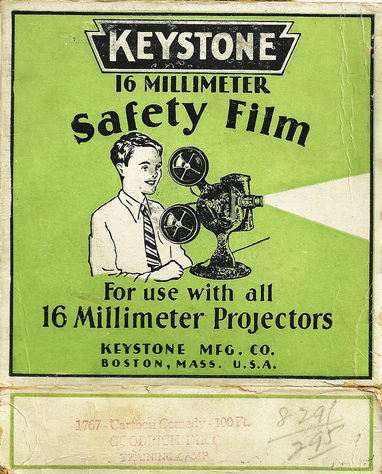

In 1932, J. R. Bray sold a large number of nitrate negatives to the Keystone Manufacturing Company of Boston for use in the toy film or "home movie" market. Keystone had been dabbling in 35mm toy projectors and film clips since 1920, and was looking for film product to market together with its 16mm projectors. Since by this time, there was very little commercial value for silent films on the theatrical circuit, Bray sold Keystone its negatives for a mere $30.00 apiece.

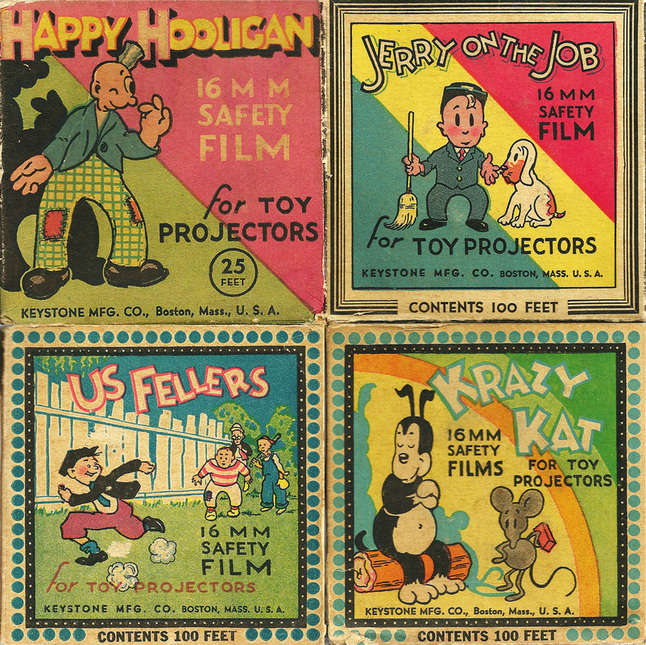

Keystone began printing and distributing some of the films in 1932, but these early prints are usually of a poor quality with focus problems. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Keystone started offering the bulk of the Bray purchase in higher-quality prints. While often edited, these prints are in many cases the only elements that currently survive on these titles. Strangely, to the best of our knowledge, Keystone never actually printed all of the Bray films they had purchased in 1932, representing a gap of approximately 35 non-distributed titles that are still difficult-to-impossible to view today.

Left: Keystone film box from 1932. This design was used throughout the 1930s. Middle: Generic 1940s box.

Below: Boxes from 1940 through the mid-1940s. Happy Hooligan, Jerry on the Job, Krazy Kat and Us Fellers films often had their own boxes during this period, but all the rest (and occasional examples of these series as well, depending on box inventory) were sold in generic boxes.

Dover Film Corp. (Late 1940s-1950)

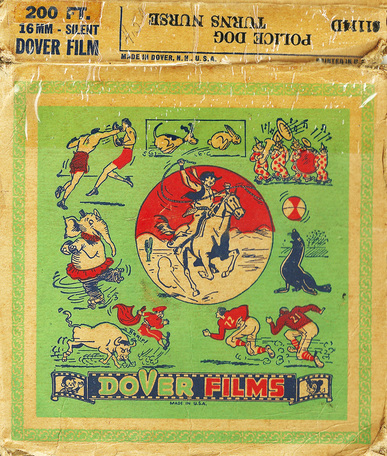

Sometime in the mid-to-late 1940s, Keystone's toy film business moved over to Dover Film Corporation, located in Dover, New Hampshire. We have as yet been unable to determine whether Dover was a subsidiary of Keystone or an entirely separate company.

Although a short-lived venture, Dover's Bray initiative offered more titles from Keystone's 1932 Bray purchase than Keystone itself ever did. That said, most batches of Dover Bray prints were very poorly made. Dover used unmarked film stock and processed it badly, leaving a grainy, yellowish, thick stock with a decent-at-best image. In terms of collecting and archiving, the older Keystone prints are almost always better quality; but then, the handful of titles sold only by Dover have been a valuable element in our research, even if clarity of image is not visually superior.

Right: Example of a Dover Films box for a 200 foot subject.

Bell and Howell (1920s-1930s)

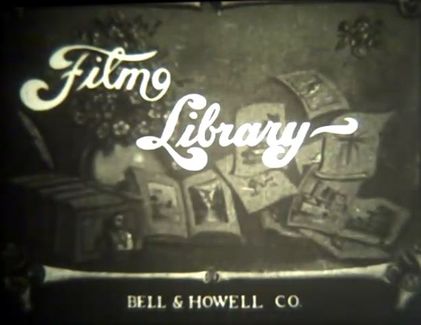

Bell and Howell seems to have been the first outfit to offer Bray cartoons in 16mm purchase catalogs. The first such instance occurred in the late 1920s, when Bell and Howell's home-use "Filmo Library" was at the peak of its popularity. Bell and Howell's "Filmo" prints were reminiscent of Kodascope Library's offerings: they had new Filmo introductory titles and the prints were mostly amber-tinted. This first Bell and Howell Bray offering comprised only a small handful of Bobby Bumps titles, edited down to a uniform 100 feet apiece.

In the mid-1930s, Bell and Howell began offering 16mm sound-on-film subjects for outright purchase; a distinctly separate catalog from the Filmo Library, and not bearing the Filmo brand name. It was at this time that J. R. Bray commissioned twelve Dinky Doodle and Pete the Pup cartoons to be "sounded": that is to say, having new soundtracks added to the originally silent films. These new sound editions appeared in the Bell and Howell sound films catalog.

Only one example of the "sounded" films currently circulates: Dinky Doodle and Red Riding Hood, in a poor condition video transfer. More Dinky Doodle films with title cards from this era have also surfaced, though the prints are silent. Some of the earlier Filmo Bobby Bumps prints have been viewed for this project, but remain somewhat elusive.

Above: Filmo Library introductory title card, circa 1928.

In the mid-1930s, Bell and Howell began offering 16mm sound-on-film subjects for outright purchase; a distinctly separate catalog from the Filmo Library, and not bearing the Filmo brand name. It was at this time that J. R. Bray commissioned twelve Dinky Doodle and Pete the Pup cartoons to be "sounded": that is to say, having new soundtracks added to the originally silent films. These new sound editions appeared in the Bell and Howell sound films catalog.

Only one example of the "sounded" films currently circulates: Dinky Doodle and Red Riding Hood, in a poor condition video transfer. More Dinky Doodle films with title cards from this era have also surfaced, though the prints are silent. Some of the earlier Filmo Bobby Bumps prints have been viewed for this project, but remain somewhat elusive.

Above: Filmo Library introductory title card, circa 1928.

The Bray Studios: Television (1948-mid 1970s)

Bray cartoons comprised what might have been the earliest collection of "outdated" backlog films packaged for the blossoming medium of television. As early as 1936, J. R. Bray was experimenting with the addition of music tracks to some of his studio's cartoons. This may very well have been the result of Bray's having seen other silent films shown on early experimental television stations, some of which operated in New York City in the late 1930s. As most media historians know, television did not really flourish until after World War II.

By 1948, when television finally started to become mainstream, hardly any product was immediately available to fill timeslots on the air. Bray spearheaded an effort to offer cartoons to TV stations. This involved corresponding with Keystone Manufacturing and Dover Film Corporation for the purpose of buying back the cartoons Bray had sold off to them years earlier. The nitrate negatives were re-purchased with ease, although a handful had deteriorated by this point. Bray complained to Dover that the negatives had been stored poorly, abused, and mutilated. He claimed that the original negatives tore and shred as they went through the only machine in New York City that could handle shrunken films. However, many of the films were successfully copied in new prints.

These 'repatriated' subjects, combined with some films Bray had kept in his vault all along, made up the Bray Cartoons package that was subsequently offered to stations internationally throughout the 1950s. New generic main and end titles were filmed for most of the subjects in order to maintain brand recognition. Most of the films were offered with added soundtracks, which were either public domain classical tunes or - in the case of many Out of the Inkwell and Dinky Doodle titles - campy narration performed by Allen Swift and others. In the case of the narrated shorts, intertitles were removed from the films and their content usually made its way into the new, spoken narration.

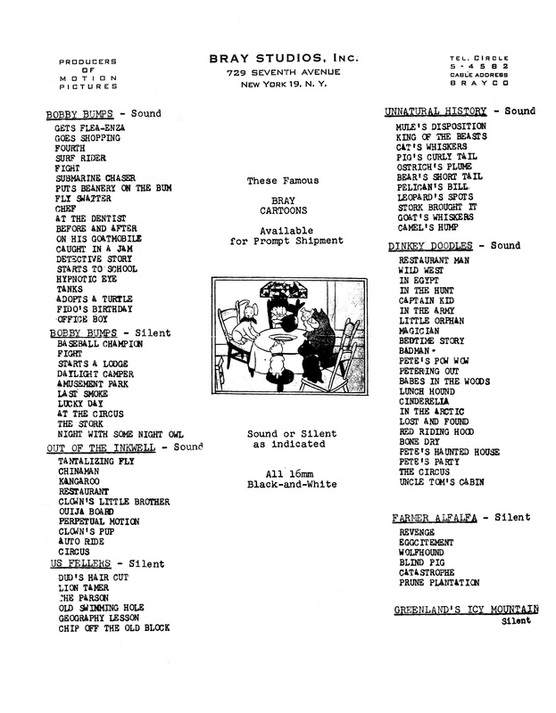

Above: Bray Cartoons sale sheet for TV stations, circa 1950.

By 1948, when television finally started to become mainstream, hardly any product was immediately available to fill timeslots on the air. Bray spearheaded an effort to offer cartoons to TV stations. This involved corresponding with Keystone Manufacturing and Dover Film Corporation for the purpose of buying back the cartoons Bray had sold off to them years earlier. The nitrate negatives were re-purchased with ease, although a handful had deteriorated by this point. Bray complained to Dover that the negatives had been stored poorly, abused, and mutilated. He claimed that the original negatives tore and shred as they went through the only machine in New York City that could handle shrunken films. However, many of the films were successfully copied in new prints.

These 'repatriated' subjects, combined with some films Bray had kept in his vault all along, made up the Bray Cartoons package that was subsequently offered to stations internationally throughout the 1950s. New generic main and end titles were filmed for most of the subjects in order to maintain brand recognition. Most of the films were offered with added soundtracks, which were either public domain classical tunes or - in the case of many Out of the Inkwell and Dinky Doodle titles - campy narration performed by Allen Swift and others. In the case of the narrated shorts, intertitles were removed from the films and their content usually made its way into the new, spoken narration.

Above: Bray Cartoons sale sheet for TV stations, circa 1950.

TV consumption of the Bray cartoons seems to have peaked between 1950 and 1956, with broadcasts on several stations across the United States and in some foreign territories as well. The cartoons' notable TV appearance occurred just prior to 1950, however, on "Uncle Fred" Sayle's Junior Frolics, broadcast in New York City. As would become the standard for children's shows, Sayles would pick a cartoon or two from the station library, then ad-lib narration for silent prints or for shorts with musical tracks.

In the mid-1950s, TV stations still had few cartoon packages to choose from, and the Bray cartoons enjoyed frequent airtime. But new packages were becoming available in the latter half of the decade: Terrytoons, Looney Tunes, and the like. In 1957, the Bray TV prints' last remaining large-scale licensee declined to renew its lease of the films, writing to Bray that they now preferred the "fresh new color Paramount cartoons": probably the U.M.&M. package of Paramount cartoons, including Fleischer's Color Classics, George Pal's Puppetoons, and Famous Studios' Little Lulu.

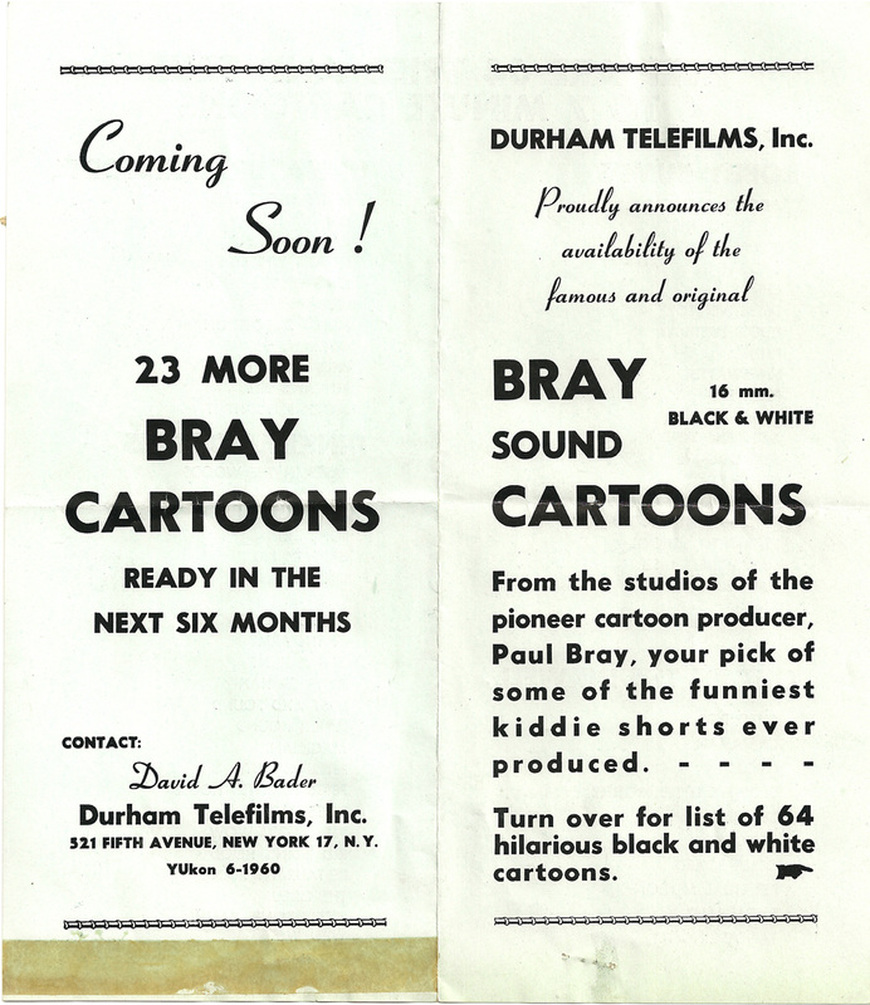

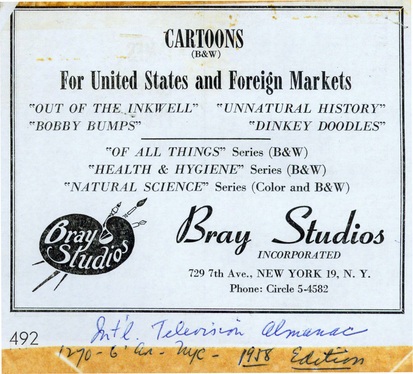

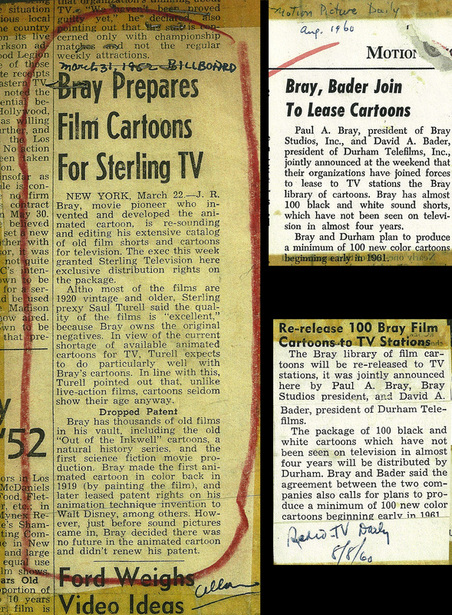

Judging by the two articles reprinted at left, the Bray cartoons received little-to-no airtime between 1956 and 1960. In 1960, however, a new marketing initiative was launched after an agreement between Paul Bray Jr. - J. R.'s grandson, now president of the company - and David A. Bader of Durham Telefilms. Interestingly, Bray and Durham also announced plans to produce new color cartoons under the Bray name, though nothing ever came of this.

It is also unlikely that the 1960 marketing campaign was very successful, as all the major TV packages of newer sound cartoons were available by this time; they would clearly have won in competition with the older Bray product.

To his credit, Paul Bray Jr. kept the films available for lease or purchase over the years that followed, but interest in the subjects was by now very low. Italian TV network RAI purchased a few titles for an animation retrospective in the mid-1970s. Walter Lantz requested a print of Dinky Doodle and Little Red Riding Hood, his favorite Dinky short, in the early 1980s and was not charged for the print. Right up to the end, Bray made some five-dozen pivotal early animated films available; but a surprising lack of interest from the era's historians resulted in the films' effective oblivion from that point forward.

Image, clockwise from left: March 31, 1952 Billboard article mentioning a brief history of the Bray films and discussing an agreement for Saul Turell (later co-founder of Janus Films) of Sterling Television to distribute the Bray cartoon package; August 1960 piece in Motion Picture Daily discussing the Bray-Durham agreement; August 8, 1960 article rehashing the same Bray-Durham information.

In the mid-1950s, TV stations still had few cartoon packages to choose from, and the Bray cartoons enjoyed frequent airtime. But new packages were becoming available in the latter half of the decade: Terrytoons, Looney Tunes, and the like. In 1957, the Bray TV prints' last remaining large-scale licensee declined to renew its lease of the films, writing to Bray that they now preferred the "fresh new color Paramount cartoons": probably the U.M.&M. package of Paramount cartoons, including Fleischer's Color Classics, George Pal's Puppetoons, and Famous Studios' Little Lulu.

Judging by the two articles reprinted at left, the Bray cartoons received little-to-no airtime between 1956 and 1960. In 1960, however, a new marketing initiative was launched after an agreement between Paul Bray Jr. - J. R.'s grandson, now president of the company - and David A. Bader of Durham Telefilms. Interestingly, Bray and Durham also announced plans to produce new color cartoons under the Bray name, though nothing ever came of this.

It is also unlikely that the 1960 marketing campaign was very successful, as all the major TV packages of newer sound cartoons were available by this time; they would clearly have won in competition with the older Bray product.

To his credit, Paul Bray Jr. kept the films available for lease or purchase over the years that followed, but interest in the subjects was by now very low. Italian TV network RAI purchased a few titles for an animation retrospective in the mid-1970s. Walter Lantz requested a print of Dinky Doodle and Little Red Riding Hood, his favorite Dinky short, in the early 1980s and was not charged for the print. Right up to the end, Bray made some five-dozen pivotal early animated films available; but a surprising lack of interest from the era's historians resulted in the films' effective oblivion from that point forward.

Image, clockwise from left: March 31, 1952 Billboard article mentioning a brief history of the Bray films and discussing an agreement for Saul Turell (later co-founder of Janus Films) of Sterling Television to distribute the Bray cartoon package; August 1960 piece in Motion Picture Daily discussing the Bray-Durham agreement; August 8, 1960 article rehashing the same Bray-Durham information.