Max Fleischer's Series

by Ray Pointer, ©2011

By the time Winsor McCay’s landmark animated film, GERTIE THE DINOSAUR (1914), played in vaudeville, the Bray Studio was regularly releasing commercially-produced animated films to movie theaters. Bray’s dominance in the field was based largely on patents for cel animation production; patents that he controlled along with another cartoonist, Earl Hurd, under the Bray-Hurd Process Company. Their combined patents greatly reduced the time and labor associated with McCay’s films. And while the Bray shorts were not as artistic or accomplished in execution, they were commercially successful -- beginning with Bray’s creation, COLONEL HEEZA LIAR, the first fully animated cartoon series.

The Bray Studio quickly became a major hub of activity, attracting many other cartoonists who entered the blossoming field of animation. In order to fill a demand for new cartoons each week, Bray set up four units that worked on a staggered schedule, making cartoons that each took a month to complete. Since the schedule enabled a new cartoon to be ready each week, this production overlap resulted in a steady release flow.

Max Fleischer came to the Bray Studios in 1916, after a chance meeting with J. R. Bray in an anteroom to Adolph Zukor’s office. At the time, Fleischer had spent two years trying to interest distributors in cartoons made with the Rotoscope, Fleischer's invention for copying live motion in animation. Bray was already acquainted with Fleischer from their days as cartoonists with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Now Bray informed Max that he had a distribution contract with Paramount, and Max joined the Bray team as an artist and production manager.

While Max's primary value to Bray was as a technical illustrator, Fleischer was also put to work as an animator on some of the HEEZA LIAR cartoons. While test films of Fleischer's Rotoscope concept were considered as source material for a series, plans were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I.

Above: Portrait of Max Fleischer taken in 1919.

The Bray Studio quickly became a major hub of activity, attracting many other cartoonists who entered the blossoming field of animation. In order to fill a demand for new cartoons each week, Bray set up four units that worked on a staggered schedule, making cartoons that each took a month to complete. Since the schedule enabled a new cartoon to be ready each week, this production overlap resulted in a steady release flow.

Max Fleischer came to the Bray Studios in 1916, after a chance meeting with J. R. Bray in an anteroom to Adolph Zukor’s office. At the time, Fleischer had spent two years trying to interest distributors in cartoons made with the Rotoscope, Fleischer's invention for copying live motion in animation. Bray was already acquainted with Fleischer from their days as cartoonists with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Now Bray informed Max that he had a distribution contract with Paramount, and Max joined the Bray team as an artist and production manager.

While Max's primary value to Bray was as a technical illustrator, Fleischer was also put to work as an animator on some of the HEEZA LIAR cartoons. While test films of Fleischer's Rotoscope concept were considered as source material for a series, plans were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I.

Above: Portrait of Max Fleischer taken in 1919.

Bray sent Max and Jack Leventhal, head of the Bray Technical Division, to Fort Sill in Oklahoma to supervise the production of the first training films produced for the Armed Forces. Subjects included “How to Operate a Stokes Mortar,” “How to Fire the Lewis Machine Gun,” “Submarine Mine Laying,” and “Contour Map Reading.” These films established the value of film as an effective educational tool, leading to a huge demand for educational and advertising films after the Armistice. The Bray Studio became the leader in this field, with many film production contracts for the Army and Navy that lasted for decades.

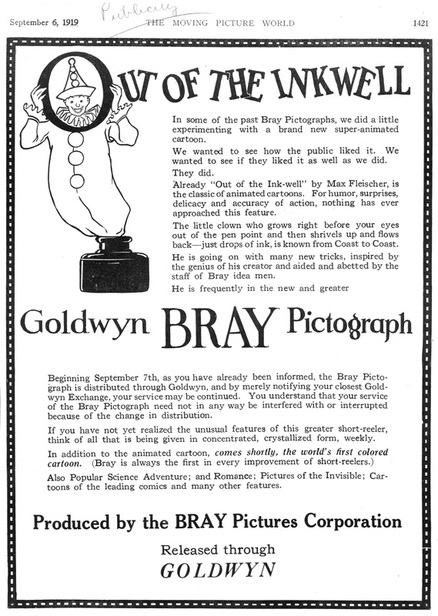

When Fleischer and Leventhal returned to in-house Bray work, a series based on Fleischer’s Rotoscope concept was considered for inclusion in Bray’s screen magazine reel, the Bray Pictograph, initially distributed by Paramount. Following the war, Bray negotiated a new contract with the Goldwyn Company. And it was during this period -- beginning in 1918 -- that Fleischer’s animation concepts started to become entries in the Pictograph.

The first three “Out of the Inkwell” shorts were copyrighted as Pictograph elements on June 4, 1918; March 24, 1919; and April 23, 1919, respectively. Initially released only under the “Inkwell” series title, they were later reissued with the episode titles Experiment No. 1, Experiment No. 2, and Experiment No. 3. But they did not actually constitute Fleischer's first rotoscope experiments at Bray. Earlier efforts likely began years earlier with the Boy Scout semaphore flag action indicated on the Rotoscope patent drawing, since it would have been necessary to demonstrate that the device produced the results described in the application.

A second experiment was said to have been traced from the print of a Chaplin film and shown to a sales representative at Pathé. While there was no mistaking that the execution was remarkable considering that it was traced from Chaplin’s actions, Pathe’ passed on it for fear of lawsuits from Chaplin. But Pathé was interested in the potential of Fleischer’s invention and commissioned a more original subject. The result was a film of a large rooster, “The Chanticleer,” based on a hunting adventure by Theodore Roosevelt. This was rejected by Pathé.

Right: Max Fleischer, center, on the set filming Contour Map Reading

When Fleischer and Leventhal returned to in-house Bray work, a series based on Fleischer’s Rotoscope concept was considered for inclusion in Bray’s screen magazine reel, the Bray Pictograph, initially distributed by Paramount. Following the war, Bray negotiated a new contract with the Goldwyn Company. And it was during this period -- beginning in 1918 -- that Fleischer’s animation concepts started to become entries in the Pictograph.

The first three “Out of the Inkwell” shorts were copyrighted as Pictograph elements on June 4, 1918; March 24, 1919; and April 23, 1919, respectively. Initially released only under the “Inkwell” series title, they were later reissued with the episode titles Experiment No. 1, Experiment No. 2, and Experiment No. 3. But they did not actually constitute Fleischer's first rotoscope experiments at Bray. Earlier efforts likely began years earlier with the Boy Scout semaphore flag action indicated on the Rotoscope patent drawing, since it would have been necessary to demonstrate that the device produced the results described in the application.

A second experiment was said to have been traced from the print of a Chaplin film and shown to a sales representative at Pathé. While there was no mistaking that the execution was remarkable considering that it was traced from Chaplin’s actions, Pathe’ passed on it for fear of lawsuits from Chaplin. But Pathé was interested in the potential of Fleischer’s invention and commissioned a more original subject. The result was a film of a large rooster, “The Chanticleer,” based on a hunting adventure by Theodore Roosevelt. This was rejected by Pathé.

Right: Max Fleischer, center, on the set filming Contour Map Reading

Mechanics and Science Films (1918-1920)

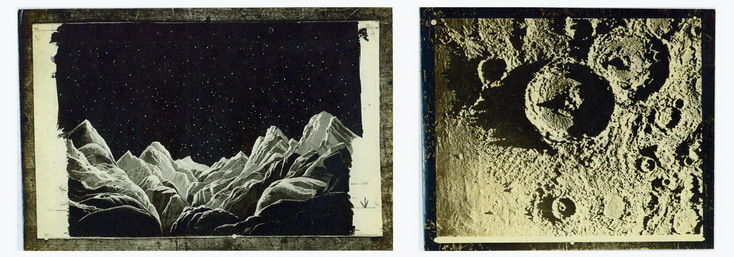

The value of film as an educational tool could not be ignored by J.R. Bray. Shorts such as Leventhal and Fleischer's The Submarine Mine Layer (1917) catered to popular interest in the war in Europe. While many subjects like this were included in the Pictograph, they saw additional value on the new educational market. Bray educational films covered many aspects of then-current information on science, engineering, mechanics, and astronomy. Several films on space exploration included All Aboard For the Moon and Hello, Mars, which were supervised by Max Fleischer.

Above: Photographs taken during production of Fleischer moon-themed films.

WWI Training Films (5)

Green: Project Print or Video

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Contour Map Reading

How to Fire the Lewis Machine Gun

How to Operate a Stokes Mortar

How to Read an Army Map

Submarine Mine Laying

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Contour Map Reading

How to Fire the Lewis Machine Gun

How to Operate a Stokes Mortar

How to Read an Army Map

Submarine Mine Laying

Mechanics and Science Films Filmography (9)

Green: Project Print or Video

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Eclipse of the Sun 7/??/1918

The Electric Bell 4/23/1919

The Elevator 6/19/1919

The Birth of the Earth 9/19/1919

Hello, Mars 1/25/1920

All Aboard for a Trip to the Moon 2/2/1920 [incomplete]

If You Could Shrink 8/31/1920

If We Lived on the Moon 9/26/1920

Through the Earth 11/8/1920

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Eclipse of the Sun 7/??/1918

The Electric Bell 4/23/1919

The Elevator 6/19/1919

The Birth of the Earth 9/19/1919

Hello, Mars 1/25/1920

All Aboard for a Trip to the Moon 2/2/1920 [incomplete]

If You Could Shrink 8/31/1920

If We Lived on the Moon 9/26/1920

Through the Earth 11/8/1920

Out of the Inkwell (1918-1921)

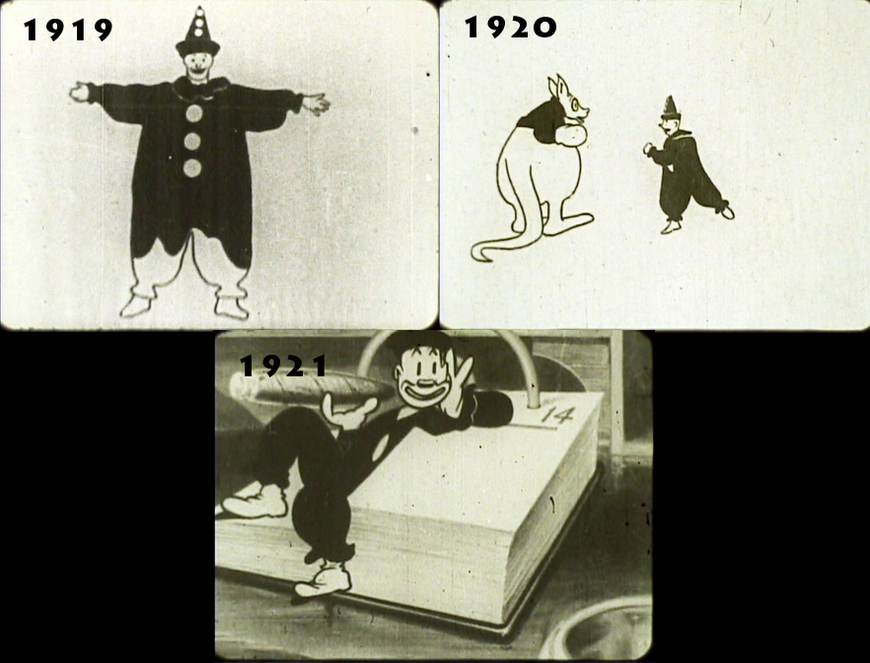

Max’s youngest brother, Dave was working as a Coney Island clown. According to family legend, the fourth Fleischer Rotoscope experiment -- later confusingly reissued as Experiment No. 1 -- resulted from Dave's casual request that Max film some of the antics from his act. This Rotoscope experiment gave birth to the series that would establish Fleischer in the animation field.

The stipulation that Bray’s units each produce one film per month necessitated that a method be found to reduce the footage required for animation. Fleischer picked up a method already realized by his Bray associate, Earl Hurd, who had applied a combination of animation and live action footage in some of his “Bobby Bumps” cartoons. This concept established the cartoonist as the on-screen creator, and the cartoon star -- Bobby, “The Clown” -- as his unruly drawing board creation. While the concept of a hand drawing animated figures was already a Bray convention, Fleischer’s innovative combination of Rotoscoped action, conventional animation, stop motion, and live action scenes made his series stand out among the other Bray short subjects.

Fleischer also had the Bray processes at his disposal, including the use of cels. To combine “The Clown” with live action footage, cel animation was overlaid upon 8 x 10" still photographs made from a live action 35mm film negative. In some early “Inkwell” films, including The Clown's Pup and The Tantalizing Fly, one can see a cut directly from “straight” live action footage to an insert filmed with overlays and still photographs. While the live action appears to freeze with a slight density shift or slight shift in image size, the effect was convincing for audiences at the time. The overlay process was an easy and inexpensive method for combining animation with the impression of a live action environment. Fleischer used the effect sparingly, but the results were striking -- as seen in The Clown's Little Brother, where “The Clown” rides a cat bareback, and in Perpetual Motion, where “The Clown” helps speed up spinning pendulums on a scientific device.

Left: Publicity for the then-established Out of the Inkwell series. Notice the reference to these films as being "a little experimenting".

The stipulation that Bray’s units each produce one film per month necessitated that a method be found to reduce the footage required for animation. Fleischer picked up a method already realized by his Bray associate, Earl Hurd, who had applied a combination of animation and live action footage in some of his “Bobby Bumps” cartoons. This concept established the cartoonist as the on-screen creator, and the cartoon star -- Bobby, “The Clown” -- as his unruly drawing board creation. While the concept of a hand drawing animated figures was already a Bray convention, Fleischer’s innovative combination of Rotoscoped action, conventional animation, stop motion, and live action scenes made his series stand out among the other Bray short subjects.

Fleischer also had the Bray processes at his disposal, including the use of cels. To combine “The Clown” with live action footage, cel animation was overlaid upon 8 x 10" still photographs made from a live action 35mm film negative. In some early “Inkwell” films, including The Clown's Pup and The Tantalizing Fly, one can see a cut directly from “straight” live action footage to an insert filmed with overlays and still photographs. While the live action appears to freeze with a slight density shift or slight shift in image size, the effect was convincing for audiences at the time. The overlay process was an easy and inexpensive method for combining animation with the impression of a live action environment. Fleischer used the effect sparingly, but the results were striking -- as seen in The Clown's Little Brother, where “The Clown” rides a cat bareback, and in Perpetual Motion, where “The Clown” helps speed up spinning pendulums on a scientific device.

Left: Publicity for the then-established Out of the Inkwell series. Notice the reference to these films as being "a little experimenting".

Out of the Inkwell Filmography (16)

Green: Project Print or Video

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Experiment No. 1 6/10/1918

Experiment No. 2 3/5/1919

Experiment No. 3 4/2/1919

The Clown's Pup 8/30/1919

The Tantalizing Fly 10/4/1919

Slides 12/3/1919

The Boxing Kangaroo 2/2/1920

The Chinaman 3/19/1920

The Circus 5/6/1920

The Ouija Board 6/4/1920

The Clown's Little Brother 7/6/1920

Poker (aka The Card Game) 10/2/1920

Perpetual Motion 10/2/1920

The Restaurant 11/6/1920

Cartoonland 2/2/1921

The Automobile Ride 6/20/1921

Gray: Print Known Elsewhere

Red: No Known Print

Experiment No. 1 6/10/1918

Experiment No. 2 3/5/1919

Experiment No. 3 4/2/1919

The Clown's Pup 8/30/1919

The Tantalizing Fly 10/4/1919

Slides 12/3/1919

The Boxing Kangaroo 2/2/1920

The Chinaman 3/19/1920

The Circus 5/6/1920

The Ouija Board 6/4/1920

The Clown's Little Brother 7/6/1920

Poker (aka The Card Game) 10/2/1920

Perpetual Motion 10/2/1920

The Restaurant 11/6/1920

Cartoonland 2/2/1921

The Automobile Ride 6/20/1921

Afterthoughts

While Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” was a welcomed installment in the Bray-Goldwyn Pictograph reels, the restrictive production budgets at Bray constricted any technical advancement of techniques. Additional problems resulted from Bray’s deal with Goldwyn, obliging Bray to produce more films than his units could easily deliver. By 1921, Bray was facing legal difficulties due to contractual breeches for non-performance and lack of delivery.

It was at this time that Bray’s major talents began departing the studio, with Max Fleischer among them. While Fleischer felt a loyalty towards John Bray, it was apparent that continued artistic and technical innovation would not be possible under the restrictive, litigious atmosphere at Bray. It was at this time that Dave won $50,000 on a horse race bet and offered an $800.00 match to Max’s investment in the startup of a new studio. Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc., would bring the brothers the freedom to explore additional technical innovations that would not have been possible at Bray.

Animation historian extraordinaire Ray Pointer is also a self-taught filmmaker, having experimented with animated cartoons from 1963 to 1973. He began his professional career at the historic Jam Handy organization in Detroit, Michigan. Ray is President and CEO of Inkwell Images, an outfit that produces educational and documentary DVD programs on early animation. Inkwell Images' "Max Fleischer's Famous Out of the Inkwell" series is a highly recommended program; most of the extant Fleischer-Bray Inkwell films can be found on Volume 1 of the collection, titled "The Bray Years."

It was at this time that Bray’s major talents began departing the studio, with Max Fleischer among them. While Fleischer felt a loyalty towards John Bray, it was apparent that continued artistic and technical innovation would not be possible under the restrictive, litigious atmosphere at Bray. It was at this time that Dave won $50,000 on a horse race bet and offered an $800.00 match to Max’s investment in the startup of a new studio. Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc., would bring the brothers the freedom to explore additional technical innovations that would not have been possible at Bray.

Animation historian extraordinaire Ray Pointer is also a self-taught filmmaker, having experimented with animated cartoons from 1963 to 1973. He began his professional career at the historic Jam Handy organization in Detroit, Michigan. Ray is President and CEO of Inkwell Images, an outfit that produces educational and documentary DVD programs on early animation. Inkwell Images' "Max Fleischer's Famous Out of the Inkwell" series is a highly recommended program; most of the extant Fleischer-Bray Inkwell films can be found on Volume 1 of the collection, titled "The Bray Years."